Podcast

Questions and Answers

What is a fracture?

What is a fracture?

Disruption or break in the continuity of bone.

How are fractures classified?

How are fractures classified?

- Communication with external environment: open (skin is broken and bone exposed) or closed (skin intact over the site)

- Complete vs. incomplete break

- Direction of the fracture line: linear, oblique, transverse, longitudinal, or spiral

- Displaced (2 ends of the broken bone are separated from each other and out of their normal positions) vs. non-displaced ("clean" break, remains in alignment)

- All of the above (correct)

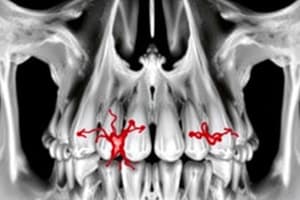

What are the different fracture types?

What are the different fracture types?

- Transverse: line of fracture extends across bone shaft at a right angle (straight across break)

- Spiral: the line of the fracture extends in a spiral direction along the bone shaft; often a sign of abuse in children

- Greenstick: incomplete fracture with 1 side splintered and the other side bent

- Comminuted: fracture with more than 2 fragments (smaller fragments appear to be floating)

- Oblique: the line of the fracture extends across and down the bone

- Impacted: two ends of broken bones are jammed together due to force

- All of the above (correct)

What are compression, pathologic, and stress fractures?

What are compression, pathologic, and stress fractures?

What are the manifestations of a fracture?

What are the manifestations of a fracture?

When a nurse suspects a fracture, what are the two priority interventions?

When a nurse suspects a fracture, what are the two priority interventions?

How is a potential fracture assessed?

How is a potential fracture assessed?

How do hip fractures present?

How do hip fractures present?

What is traction? When is it used?

What is traction? When is it used?

What are the teachings for a patient with a cast?

What are the teachings for a patient with a cast?

What are the teachings for a patient after a cast is removed?

What are the teachings for a patient after a cast is removed?

What are the nursing interventions for patients with an amputation?

What are the nursing interventions for patients with an amputation?

What is a fat emboli (description, manifestations, interventions)?

What is a fat emboli (description, manifestations, interventions)?

What is avascular necrosis?

What is avascular necrosis?

What is compartment syndrome?

What is compartment syndrome?

What is compartment syndrome? Describe the causes and manifestations.

What is compartment syndrome? Describe the causes and manifestations.

What are the complications of infection (description, manifestations, interventions) after a fracture?

What are the complications of infection (description, manifestations, interventions) after a fracture?

What are the types of burn injury?

What are the types of burn injury?

What are thermal burns (heat)?

What are thermal burns (heat)?

What are thermal burns (cold)? What are the manifestations?

What are thermal burns (cold)? What are the manifestations?

What are chemical burns?

What are chemical burns?

What is smoke and inhalation injury? What are the three types and their manifestations?

What is smoke and inhalation injury? What are the three types and their manifestations?

What are electrical burns? What are these patients at risk for?

What are electrical burns? What are these patients at risk for?

How are burns classified?

How are burns classified?

What are partial thickness burns? Describe the appearance, common causes, and structures involved.

What are partial thickness burns? Describe the appearance, common causes, and structures involved.

What are full-thickness burns? Describe the appearance, common causes, and structures involved.

What are full-thickness burns? Describe the appearance, common causes, and structures involved.

What is eschar?

What is eschar?

How does the location of burns affect the severity?

How does the location of burns affect the severity?

How are the extent of burns determined using the rule of 9's?

How are the extent of burns determined using the rule of 9's?

What are the phases of burn management?

What are the phases of burn management?

What are the pre-hospital interventions for burns? (small/large thermal and chemical burns)

What are the pre-hospital interventions for burns? (small/large thermal and chemical burns)

What is the emergent phase of burn management? When does it end? What are the main concerns?

What is the emergent phase of burn management? When does it end? What are the main concerns?

Emergent phase of burns: patho/manifestations

Emergent phase of burns: patho/manifestations

Emergent phase of burns: complications

Emergent phase of burns: complications

Emergent phase of burns: airway management

Emergent phase of burns: airway management

Emergent phase of burns: fluid therapy

Emergent phase of burns: fluid therapy

If a patient who weighs 70 kg has a TBSA of 45%, how much fluid replacement do they require?

If a patient who weighs 70 kg has a TBSA of 45%, how much fluid replacement do they require?

Emergent phase of burns: wound care

Emergent phase of burns: wound care

Emergent phase of burns: other care measures

Emergent phase of burns: other care measures

What is the acute phase of burn management? When does it end?

What is the acute phase of burn management? When does it end?

Acute phase: patho/manifestations

Acute phase: patho/manifestations

Acute phase: complications

Acute phase: complications

Acute phase: wound care

Acute phase: wound care

Acute phase: pain management

Acute phase: pain management

What is the rehabilitation phase of burn management?

What is the rehabilitation phase of burn management?

Rehabilitation phase: patho/manifestations

Rehabilitation phase: patho/manifestations

Rehabilitation phase: complications

Rehabilitation phase: complications

Flashcards

Fracture classification

Fracture classification

Fractures are classified based on communication with the external environment (open/closed), completeness of break (complete/incomplete), fracture line direction (linear, oblique, transverse, longitudinal, spiral), and displacement (displaced/non-displaced).

Transverse Fracture

Transverse Fracture

A fracture where the line of break is across the bone shaft at a right angle.

Spiral Fracture

Spiral Fracture

A fracture where the line of the fracture extends in a spiral direction along the bone shaft.

Greenstick Fracture

Greenstick Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Comminuted Fracture

Comminuted Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Oblique Fracture

Oblique Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Impacted Fracture

Impacted Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Compression Fracture

Compression Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Pathologic Fracture

Pathologic Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Stress Fracture

Stress Fracture

Signup and view all the flashcards

Fracture Manifestations

Fracture Manifestations

Signup and view all the flashcards

Fracture Priority Interventions

Fracture Priority Interventions

Signup and view all the flashcards

Hip Fracture Presentation

Hip Fracture Presentation

Signup and view all the flashcards

Femur Fracture Presentation

Femur Fracture Presentation

Signup and view all the flashcards

Traction

Traction

Signup and view all the flashcards

Cast Care Teachings

Cast Care Teachings

Signup and view all the flashcards

Post-Cast Removal Teachings

Post-Cast Removal Teachings

Signup and view all the flashcards

Amputation Nursing Interventions

Amputation Nursing Interventions

Signup and view all the flashcards

Fat Embolism Syndrome

Fat Embolism Syndrome

Signup and view all the flashcards

Study Notes

Fracture Classification

- Fractures are breaks in bone continuity.

- Classification factors include:

- Open (skin broken, bone exposed) vs. Closed (skin intact)

- Complete (full break) vs. Incomplete (partial break)

- Fracture line direction (linear, oblique, transverse, longitudinal, spiral)

- Displaced (bone ends separated) vs. Non-displaced (bone ends aligned)

Fracture Types

- Transverse: fracture line straight across the bone shaft.

- Spiral: fracture line spirals along the bone shaft (often abuse indicator in children).

- Greenstick: incomplete fracture with one side splintered and the other bent.

- Comminuted: fracture with more than two fragments.

- Oblique: fracture line across and down the bone shaft.

- Impacted: bone ends jammed together by force.

Special Fracture Types

- Compression fractures: typically in vertebrae, common in elderly due to osteoporosis; pain relieved by lying, worse with walking.

- Pathologic fractures: spontaneous breaks at diseased bone sites.

- Stress fractures: repeated stress on normal or abnormal bone (e.g., running).

Fracture Manifestations

- Localized pain and tenderness

- Decreased function (can't bear weight/use limb)

- Guarding the affected limb

- Visible deformity

- Bruising

- Crepitus (grating sound)

- Swelling

- Muscle spasms

Priority Interventions for Suspected Fracture

- CMS assessment (circulation, motion, sensation)

- Immobilization (cast, splint, wound dressing)

Assessment of Potential Fracture

- History and physical exam (past medical history, medications, treatments)

- Peripheral circulation (color, temperature, pulses, edema)

- Neurologic function (sensation, motor function, muscle spasms)

- Diagnostic tests (x-ray, CT, MRI, CBC, electrolytes, urinalysis, arteriogram if needed)

Specific Fracture Locations

- Hip fractures: leg shortens, external leg rotation.

- Femur fractures: leg may shorten, internal or external rotation.

Traction

- Application of pulling force to a body part.

- Used for: pain/muscle spasm relief, immobilization, fracture/dislocation reduction, and treating joint conditions.

- Often used in non-stable patients. This reduces soft tissue damage.

Cast Care (Teaching)

- Plaster: Hot and damp until dry (avoid covering). Handle with palm, not fingertips. Don't put directly on plastic. Immobilized for weight bearing after 36-72 hours.

- Synthetic: Lighter, waterproof, and longer-lasting than plaster.

- General: Isometric exercises, weight bearing as instructed. Monitor circulation/infection. Loose cast = decreased swelling, new cast needed.

Post-Cast Removal Care

- Wash skin gently, no lotion or scratching.

- Resume activities gradually (prevent re-fractures).

- Rest and elevate frequently.

- Limb size differences are normal.

Amputation Nursing Interventions

- General: Observe for phantom limb pain.

- Post-operative:

- Elevate amputated limb to prevent edema.

- Stump support, encouraging rest positions and ROM.

- Compression bandages until healed (24/7).

- ROM and strengthening exercises.

Fracture Complications

- Fat Embolism Syndrome: Fat globules enter circulation (often after long bone fracture) accumulating in blood vessels. Manifestations (within 24-48 hours): chest pain, tachypnea, cyanosis, dyspnea, mental status change, petechiae. Interventions: fluids, respiratory support.

- Avascular Necrosis: Interrupted blood flow to bone → death. Intervention: immediate contact with provider for surgical intervention

- Compartment Syndrome: Swelling creates increased pressure in a muscle compartment → nerve/blood flow problems. Manifestations (6 Ps): severe pain, pressure, paresthesia/weakness, pallor/coolness, paralysis, pulselessness.

- Infection: Common in open fractures (osteomyelitis). Manifestations: pain/systemic, local symptoms (swelling, warmth, tenderness). Intervention: surgical debridement and antibiotics.

Burn Types

- Thermal (heat)

- Chemical

- Smoke/Inhalation

- Electrical

Thermal Burns (Heat/Cold)

- Heat: Caused by flame, flash, scalds, or contact; severity depends on temperature and duration.

- Cold: Frostbite - tissue freezing from cold temperatures. Superficial frostbite involves shallow skin damage. Deep frostbite involves deeper tissues and may result in gangrene.

Chemical Burns

- Contact with acids, alkalis, or organic compounds; risk for eye damage if splashed.

Smoke/Inhalation Injury

- Breathing noxious chemicals or hot air. Results in upper and lower airway damage.

Electrical Burns

- Intense heat from an electric current; direct nerve and vessel damage. Potential risks: dysrhythmias, cardiac arrest, metabolic acidosis, myoglobinuria (AKI risk).

Burn Classification

- Depth

- Extent

- Location

- Patient factors (age, pre-existing conditions, circumstances of injury)

Partial Thickness Burns

- Superficial (First Degree): Erythema, mild pain, blanches upon pressure, no blisters initially.

- Deep (Second Degree): Fluid-filled vesicles; severe pain; red, shiny skin; moderate edema.

Full Thickness Burns (Third Degree)

- Dry, waxy, white, or hard skin. Loss of sensation (pain). Muscles, tendons, or bones may be involved.

Eschar

- Leathery, dead burn tissue.

Burn Location Impact

- Face/neck/chest/back = respiratory compromise risk (edema, eschar).

- Hands/feet/joints/eyes = self-care difficulties/loss of function.

- Ears/nose = risk for infection due to thin skin/blood supply.

- Perineum/buttocks = high infection risk from secretions, urine, or feces.

- Circumferential extremity burns = limited distal blood flow, compartment syndrome/nerve damage.

Rule of Nines

- Method to estimate total body surface area (TBSA) burned.

Burn Management Phases

- Emergent (prehospital+emergency)

- Acute

- Rehabilitation

Prehospital Burn Interventions

- Remove from burn source.

- Small thermal: Cool with cool water.

- Large thermal: ABCs, cool for 10 minutes (avoid ice baths), wrap in clean sheet.

- Chemical: Remove chemical, remove contaminated clothing, flush with water.

Emergent Phase of Burn Management

- Time to resolve immediate life-threatening problems (usually 72 hours).

- Main concerns: hypovolemic shock and edema.

- Ends when fluid mobilization and diuresis begin.

Emergent Phase Patho/Manifestations

- Fluid and electrolyte shifts (massive fluid shifts into interstitial, hyperkalemia, hyponatremia).

- Inflammation and healing (necrosis).

- Manifestations: hypovolemic shock, increased hematocrit, paralytic ileus, shivering, edema.

Emergent Phase Complications

- Cardiovascular (hypovolemic shock, dysrhythmias, impaired circulation, VTE, preexisting heart failure)

- Respiratory (upper/lower airway distress, preexisting conditions like pneumonia/pulmonary edema)

- Urinary (acute tubular necrosis, AKI, blockage of tubular function)

Emergent Phase: Airway Management

- ABGs, intubation if needed (burns to face or neck).

- Ventilatory support, 100% humidified oxygen.

- Positioning (semi/high fowler's).

- Surgical intervention (escharotomies, bronchoscopy).

Emergent Phase: Fluid Therapy

- IV access, lactated Ringer's solution.

- Parkland formula for fluid resuscitation (TBSA x weight x 4mL). Given half in first 8 hours, other half in the next 16.

- Hourly assessments: urine output, MAP, HR, SBP.

Acute Phase of Burn Management

- Begins with fluid mobilization and diuresis, ends when wounds heal.

- May take weeks to months.

Acute Phase Patho/Manifestations

- Diuresis, bowel sounds return.

- Emotional support.

- Healing begins (partial-thickness spontaneous vs full-thickness grafting).

- Electrolyte imbalances (hyponatremia, hypernatremia, hyperkalemia, hypokalemia).

Acute Phase Complications

- Infection

- Cardiovascular/Respiratory (prev complications - new may arise)

- Neurologic (electrolyte imbalance considerations, stress, cerebral edema)

- Musculoskeletal (contracture prevention)

- GI (stress ulcers, paralytic ileus, diarrhea, constipation)

- Endocrine (hyperglycemia)

Acute Phase: Wound Care

- Daily wound assessments, cleansing, debridement, dressing changes.

- Excision/grafting: autografts, allografts, cultured epithelial autografts, or artificial skin.

- Graft care: elevations, immobilization, protection from pressure/contamination.

Acute Phase: Pain Management

- Opioids, anxiolytics, other analgesics.

- Non-pharmacological strategies.

Rehabilitation Phase of Burn Management

- Begins when wounds significantly healed; patient engaging self-care.

- May last 7-8 months.

- Goals: functional role return, rehabilitate post-burn surgeries (functional/cosmetic).

Rehabilitation Phase Complications

- Skin/joint contractures (ROM, splinting, positioning)

- Hypertrophic scarring

Rehabilitation Phase Interventions

- Pt education (wound care, follow-up, scar management, sun protection, moisture).

- PT and OT routines.

- Emotional support, address spiritual/cultural needs.

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

- Lower: Bladder or urethra infection (cystitis/urethritis)

- Upper: Kidney infection (pyelonephritis, glomerulonephritis)

Lower UTI Symptoms

- Painful urination (dysuria)

- Frequent/urgent urination

- Suprapubic discomfort

- Cloudy/bloody urine

Upper UTI Symptoms

- Lower UTI symptoms + fever, chills, flank pain, CVA tenderness, vomiting/malaise.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Prostate gland enlargement, obstructing urine outflow.

- Common in men over 50.

BPH Clinical Manifestations

- Frequent/urgent urination

- Painful urination (dysuria)

- Nighttime urination (nocturia)

- Weak/intermittent urine stream

- Difficulty initiating urination

- Dribbling

Transurethral Resection of the Prostate (TURP)

- Procedure to remove prostate tissue.

- Performed when BPH is obstructive and other treatments are ineffective.

Continuous Bladder Irrigation (CBI)

- Maintains urine drainage after TURP. Normal saline is continuously infused into and drained from the bladder.

CBI Nursing Management

- Assess for bleeding/clots.

- Monitor catheter patency (intake/output, bladder spasms).

- Monitor drainage (increased blood/clots).

Post-TURP/CBI Care

- Pain management.

- Hemorrhage monitoring (VS changes, red blood).

- Infection monitoring.

- Meds/relaxation techniques, bladder spasms irrigation.

- Kegel exercises, fluid intake (2000-3000 mL), prevent constipation. Avoid heavy lifting/driving/sex.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

- Rapid kidney function loss, increased serum creatinine, decreased urine output.

Prerenal AKI Causes

- Hypoperfusion (reduced renal blood flow & GFR): hypovolemia, decreased cardiac output, shock, etc.

Intrarenal AKI Causes

- Direct kidney tissue damage (ischemia, nephrotoxins, etc.).

- Acute Tubular Necrosis: necrotic tubular epithelial cells, causing obstruction/impaired function (often ischemia or nephrotoxin-induced).

Postrenal AKI Causes

- Mechanical obstruction of urine outflow.

- BPH, prostate cancer, calculi, trauma, tumors.

AKI Phases

- Oliguric, Diuretic, Recovery

Oliguric Phase

- Decreased urine output (<400 mL/day).

- Lasts 10-14 days (longer = poor prognosis).

- May have non-oliguric renal failure (>400 mL/day).

Oliguric Phase Manifestations

- Fluid overload, edema, hypertension, heart failure, pulmonary edema.

- Waste product buildup (increased BUN/creatinine).

- Electrolyte imbalances (hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia).

- Metabolic acidosis.

- Anemia, platelet abnormalities.

- Neurological changes (waste product buildup).

Diuretic Phase

- Kidneys recover excretion but not concentration ability.

- Urine output 1-5 L/day.

- Lasts 1–3 weeks

- Uremia persists (high BUN/creatinine)

- Fluid and electrolyte loss = risk for hypovolemia, hypotension.

Recovery Phase

- GFR increases.

- BUN/creatinine decrease (plateau, then decrease).

- Full recovery can take up to 12 months.

AKI Medications

- Fluids & Electrolytes: IV fluids, volume expanders, diuretics. Dialysis for overload, electrolyte imbalances.

- Hyperkalemia: IV insulin, sodium bicarbonate, calcium gluconate, kayexalate.

- Renal dosing of medications is required to prevent further damage

AKI Diet

- Moderate protein, restrict sodium/potassium per lab values, adequate calories (carbs/fats).

- Small, frequent meals; limited fluids.

Chronic Kidney Disease Electrolyte Imbalances

- Hyperkalemia, hypermagnesemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and possibly sodium shifts. (all above normal range is cause for concern)

CKD Electrolyte Treatment

- Phosphate binders, vitamin D supplements, calcium supplements.

- Potassium management (IV insulin, sodium bicarb, kayexalate, calcium gluconate).

- Fluid/diet modifications.

Dialysis Precautions

- Affected arm precautions (no BP, blood draws, IVs, heavy lifting).

- Monitor dialysis site for thrill/bruit.

- Sterile procedure for peritoneal dialysis (PD).

Types of Shock

- Cardiogenic

- Hypovolemic

- Distributive (neurogenic, anaphylactic, septic)

Cardiogenic Shock

- Impaired heart pumping, reduced cardiac output due to MI, cardiomyopathy, etc.

Cardiogenic Shock Treatment

- Restore blood flow to myocardium (oxygen, treat cause e.g. thrombolytics, stenting, valvular replacement).

- Hemodynamic monitoring.

- Drug therapy: vasodilators, diuretics.

Hypovolemic Shock

- Loss of intravascular fluid—absolute (hemorrhage, GI loss) or relative (third spacing, increased capillary permeability).

Hypovolemic Shock Treatment

- Stop fluid loss, restore volume (vascular access & fluids – crystalloids, colloids, blood).

Neurogenic Shock

- Massive vasodilation following spinal cord injury (T5 or above) or spinal anesthesia.

Neurogenic Shock Treatment

- Fluids cautiously; hypotension often not from fluid loss.

- Treat hypotension & bradycardia (vasopressors, atropine).

- Monitor for hypothermia.

Anaphylactic Shock

- Severe hypersensitivity reaction, massive vasodilation, increased capillary permeability.

Anaphylactic Shock Treatment

- Epinephrine (vasoconstriction, increases BP, bronchodilation).

- Airway management (intubation).

- Fluid replacement (crystalloids).

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl).

Septic Shock

- Systemic inflammatory response to infection (sepsis) + hypotension despite fluid resuscitation

- Vasodilation, blood flow maldistribution, myocardial depression.

Septic Shock Treatment

- Aggressive fluid replacement (crystalloids).

- Hemodynamic monitoring.

- Vasopressors if fluid resuscitation inadequate.

- Antibiotics (within first hour).

- Glucose/stress ulcer/DVT prophylaxis.

Stages of Shock

- Compensatory (subtle signs, attempts at homeostasis).

- Progressive (failing compensatory mechanisms, low BP).

- Refractory/Irreversible (organ failure, recovery unlikely).

Adrenal Cortex Hormones

- Glucocorticoids (cortisol): metabolism regulation, increase blood glucose

- Mineralocorticoids (aldosterone): sodium/potassium balance

- Androgens (sex hormones): muscular/sexual development

Cushing Syndrome

- Chronic exposure to excessive adrenal hormones (typically glucocorticoids).

- Causes: exogenous corticosteroids, pituitary adenoma.

Cushing Syndrome Symptoms

- Glucocorticoid excess: weight gain, moon face, buffalo hump, hyperglycemia, muscle wasting, osteoporosis, thin skin, delayed wound healing, mood changes.

- Mineralocorticoid excess: hypertension, hypokalemia.

- Androgen excess: acne, hirsutism, menstrual issues, feminization in males.

Addison's Disease

- Adrenal hormone insufficiency.

- Most commonly autoimmune; can occur after steroid discontinuation.

Addison's Disease Manifestations

- Anorexia, nausea, weakness, fatigue, weight loss.

- Hyperpigmentation (excess ACTH).

- Orthostatic hypotension.

- Salt craving.

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

- Sudden, progressive form of acute respiratory failure. Damaged alveolar-capillary membrane, causing fluid build-up in alveoli.

ARDS Nursing Interventions

- Oxygen therapy (mechanical ventilation).

- Prone positioning.

- Cardiac output/tissue perfusion maintenance.

- Fluid balance management.

- Nutritional support.

- Skin integrity assessment.

- ABGs

Iron Deficiency Anemia

- Lack of iron → impaired RBC synthesis; causes blood loss, lack of intake/absorption, hemolysis, or pregnancy.

- Symptoms: general anemia symptoms, brittle nails, swollen tongue, cracked mouth.

Iron Deficiency Anemia Treatment

- Iron supplements (ferrous sulfate, take with vitamin C).

- Increased dietary intake (iron-rich foods).

Sickle Cell Disease

- Genetic, autosomal recessive disorder leading to sickle-shaped RBCs. Abnormal hemoglobin (HbS) present.

Sickle Cell Crisis Prevention Teaching

- Avoid infections.

- Stay hydrated.

- Avoid high altitudes.

- Prompt medical attention for episodes.

- Pain management, medications.

Cobalamin Deficiency Anemia

- B12 injections.

- Increased dietary intake (B12 rich foods).

Organ Rejection

- Hyperacute: Immediate vessel destruction; antibodies (high PRA) responsible, fatal.

- Acute: T-lymphocytes attack organ (first 6 months). Treatable with immunosuppressants.

- Chronic: Fibrosis and scarring over time, irreversible organ damage.

Organ Rejection Symptoms

- Fever, malaise, aches, pain at transplant site, signs of organ failure.

Calcineurin Inhibitors (e.g., Cyclosporine, Tacrolimus)

- Suppress cytotoxic T cell activation.

- Side effects: nephrotoxicity (monitor creatinine/BUN), hypertension.

Cytotoxic Drugs (e.g., Sirolimus, Azathioprine, Mycophenolate)

- Inhibit T/B cell proliferation.

- Side effects: gastrointestinal toxicity (N/V, diarrhea).

Studying That Suits You

Use AI to generate personalized quizzes and flashcards to suit your learning preferences.